Out-of-bounds read

Plugging the holes and stopping memory leakage in its tracks

~20mins estimatedC++

What is an out-of-bounds read?

Out-of-bounds read is a type of vulnerability found in memory unsafe languages that are often the result of the lack of bounds checking when data is accessed via some index controlled by user input.

The result of an out-of-bounds read vulnerability is usually leakage of sensitive data in memory, such as encryption keys, passwords, and session cookies. It has two different variations: if the accessed memory is over the bounds of the intended buffer, then it's a buffer over-read; if the accessed memory is under (before) the address of the intended buffer, it's a buffer under-read. In some scenarios, both conditions can apply and be exploited.

About this lesson

In this lesson, you will learn about the out-of-bounds read vulnerability and how to protect your applications against it by improving memory safety. We will step into the shoes of Alex, a greybeard sysadmin who wrote his own encrypted password vault in C++, then forgot the password to it, and how he recovered the secrets inside by exploiting a flaw in his own code.

Finley hasn't logged into one of his $10 SSH servers, which he had set up in the cloud, for a while. He remembered that he had put the password somewhere, but ever since he had ditched all his password managers (because he didn't trust them), his secrets had been scattered all over the place. He even remembered that, in one impulsive afternoon, he had written his own encrypted secret vault and deployed it in his internal network, after seeing yet another password manager breach.

Connecting to his makeshift secret vault via netcat, he smiles at its simple interface. He hits 2 on his keyboard to read the note and the 2 again to open the SSH password.

Hmmm... the password...

Finley did not remember the encryption password. However, after a short review of the code, he realized that he had made a mistake when building this in a hurry and left a loophole he could exploit with a simple Python script:

Upon running this script, he quickly scrolled through the output and found a partial piece of his password, "uperS3cureNotes":

Thinking along the lines of his password-making conventions, Finley realized the complete password must be "SuperS3cureNotes". With that, he successfully decrypted the note and regained access to his SSH server.

Let's see how Finley figured out how to retrieve his old notes encryption password from the vault. In a hurry, he made the note storage structure quite simple, with a simple class that stored statically allocated char arrays for the title and content of the note:

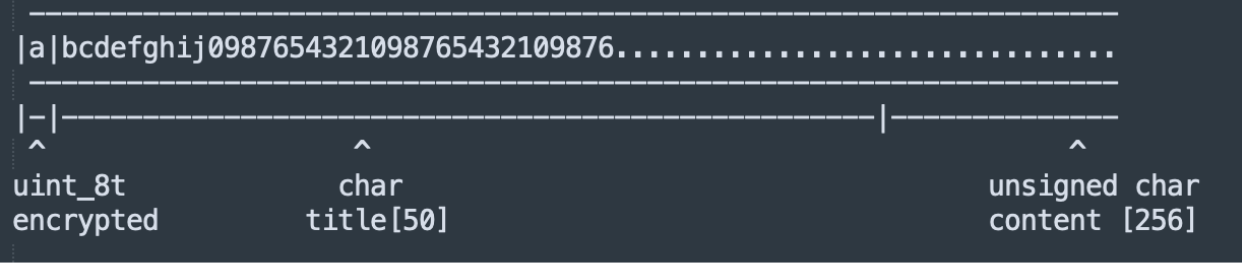

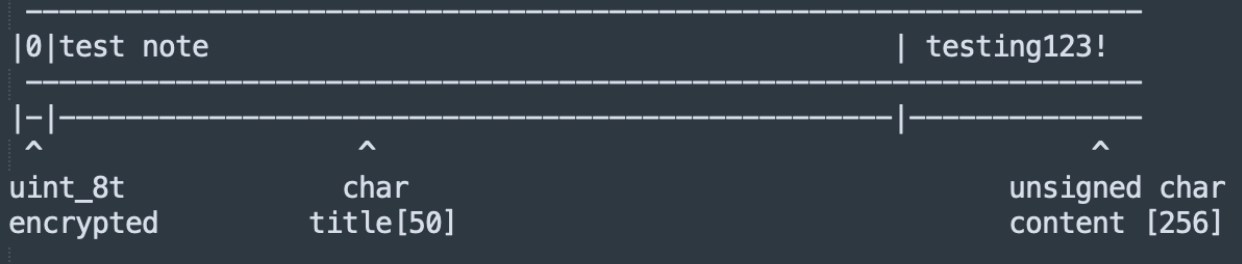

For storing notes that are less sensitive, each note starts with an 8-bit integer that denotes its encryption. Finley thought that using an integer would help him implement stronger types of encryption later on, but for now, it's basically a 0 or a 1 denoting whether or not that note is encrypted.

Below are code snippets from the main function, which takes the encryption password from the VAULT_PASS environment variable. Then it loads the notes vault and prompts the user for action.

Finley realized that one of the mistakes he made was that when taking the user's selection on which notes to read, he used the int type to store the number from the output of atoi (which is the correct return type); however, because the int type is signed by default, it allows the storage of negative as well as positive values.

This is the implementation of the read_note function, which takes the array of notes and reads the one specified at the index, and decrypts it with a password if necessary:

As seen above, the index parameter to read_note is also an int. This means if the index was a negative number, it would read the contents of memory before the first note's pointer, and access that address in memory as if it were an object of the Note class:

Select note to read: -20title: !��this note is encrypted! enter password:For any block of memory that the process can read before the notes pointer, it will be treated like a Note object, like so:

That means for a normal note, it'd look like this, with the title and contents (beginning with the byte 0x00 or 0x01, depending on if it's encrypted):

But for the variable vault_pass, which is stored in memory, it would have the first character of the password "S" in the encrypted field, and therefore not leaked along with the rest of the string:

Since there is no bounds checking on the index of which note to read, an attacker could traverse +/-N blocks of memory at a time (where N is the approximate size of a Note object in memory) and leak any content with the first printf call in the read_note function until it hits a NULL byte (since strings in printf will stop at a NULL byte).

The impact of out-of-bounds read

The impact of an out-of-bounds read vulnerability is usually the leakage of sensitive data from memory. Depending on the application, this could mean different things. In the case of any system that requires authentication or uses sensitive encryption material (such as the vault password example above), it could allow the attacker to perform an authentication bypass.

A recent, infamous example of an out-of-bounds read is "CitrixBleed" (CVE-2023-4966), a critical vulnerability in the Citrix Netscaler gateway product, which, depending on configuration, provided virtual remote desktop access to unauthenticated users. The vulnerability stemmed from a lack of bounds checking before a large HTTP response was sent to the client after user-controlled variables were put into a snprintf call. The return value (bytes written) of the snprintf call was used to determine how many bytes to send from a memory buffer. With a sufficiently large Host header, an attacker could demand an overly large response from the server, leading to the leakage of sensitive data such as session tokens, which they can abuse to bypass any authentication and access virtual desktops from the target organization. The mass exploitation of CitrixBleed led to an estimated 20,000 devices being compromised, many of which were compromised by ransomware groups.

The key to fixing out-of-bounds errors is to perform bounds checking when data is accessed. It is important when bounds checking to pay attention to the type of the index variable (for example, whether or not it is signed), and check both upper and lower bounds. Buffer under-reads can usually be mitigated by making sure the index is not negative.

Here's an example of bounds checking before the read_notes function is called to ensure that the note accessed is a valid note and not some random blocks of memory:

The index >= note_count check (instead of index > note_count) is important to eliminate an "off-by-one" over-read. For example, if there are two notes, then only indices 0 and 1 are valid; if index 2 were accessed, it would be one over the bounds of the notes array. Off-by-ones are a common cause of out-of-bounds reads due to the ease of confusion with sizes, particularly with buffer sizes of NULL-terminated strings (e.g., the string "hello" is five characters long but requires a sixth character to hold the NULL byte, or it won't be terminated properly).

Test your knowledge!

Keep learning

Learn more about out-of-bounds read with these resources:

- The CWE page matching this vulnerability type

- In-depth analysis of CitrixBleed, a critical vulnerability based on out of bounds read

- The CWE for off-by-one vulnerability